Abstract:

This article examines the territorial rivalry and Jihadist Strategy between Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) and the Islamic State in the Sahel Province (ISSP) in the Sahel-Sahara region. It provides a comparative analysis of the development, ideologies, tactics, and governance systems of both jihadist movements. The article acknowledges that ethnic dynamics, regional rivalries, and the military engagement of local and global stakeholders shape the conflict setting and the capacity and expansion of the groups. Using the latest updates, the article assesses what the ongoing competition between both groups means for regional stability and security. Finally, the article looks to the future and explores possible outcomes and challenges facing local and regional interests in a world where local, regional, and global factors have engaged the influence of Jihadist insurgent movements in the Sahel.

Key words: JNIM, ISSP, Sahel-Sahara, AL-Qaeda, Islamic State Organization, Ethnic Dynamics, Macina.

Introduction:

In recent years, the Sahel-Sahara region has become one of the most important fronts of jihadist insurgent activity. The region has long suffered from chronic instability, but in this period of insurgent takeover, there has been intense competition between two leading jihadist organizations: Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), an al-Qaeda affiliate, and the Islamic State in the Sahel Province (ISSP or ISGS.[1]), affiliated with the Islamic State. The emergence of these two groups and their rapid expansion of operational capacity have stemmed from the unique way they have adopted and acted on their ideologically distinct and tactically different methods of operation.

The implications of this rivalry are significant for regional security dynamics, governance frameworks, and humanitarian conditions in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso, as well as in neighbouring states. This article provides an investigation of the respective historical paths, strategic motives, ethnic composition, governance mechanisms, and territorial control of JNIM and ISSP. It discusses how their rivalry influences local and regional stability, describes the relational patterns with communities experiencing violence, and considers the wider geopolitical consequences of their rivalry.

Historical Background of Each Group

Formation and Leadership of JNIM

The Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) was officially announced on March 3, 2017, after four major jihadist factions in the region announced their merger into a unified umbrella group under this name. This alliance included the Tuareg-dominated Ansar Dine movement; the Fulani-dominated Macina Liberation Front led by Mohamed Koufa; Al-Mourabitoun, a former al-Qaeda affiliate in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) led by Mokhtar Belmokhtar; Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)-Sahara branch led by Jamal Okacha; and Ansar Sharia in Mali, which includes Arab elements in northern Mali.[2]

Similar to Al-Mourabitoun and Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, it was the first armed jihadist group in the Sahel and Sahara, dating back to the Black Decade in Algeria in the 1990s.

The remaining groups were founded in 2012. He received weapons training in Libya during the rule of Muammar Gaddafi as part of the Tuareg Green Battalion and fought during the Lebanese Civil War against armed militias and the Israeli army. He then led the Popular Movement of Azawad and its revolution in Mali in 1990. In 1992, after concluding peace with the Malian government, he was appointed Consul General in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.[3]

After that, Iyad Ghali’s name disappeared, only to reappear in 2000 as a negotiator and mediator for the release of European nationals held captive by Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. It is worth noting that the most important source of Ag Ghaly’s enormous wealth was through these operations, for which he received a large commission[4].

Ag Ghaly’s name returned to prominence in 2012 with his announcement of the establishment of the Ansar Dine group, linked to Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), and the establishment of the Islamic Emirate of Mali. During this period, he allied with the Al-Mourabitoun Movement and the Azawad Liberation Movement, seizing control of northern Mali. The French army intervened at the time, expelling them from the cities they had seized, and they returned to the desert.[5]

The Front for the Liberation of Macina was founded in 2015 by Amadou Koufa, a preacher from the Peuls. The group claimed its existence following operations carried out in central and southern Mali. The Macina Movement is currently considered the spearhead of al-Qaeda in West Africa.

It is noteworthy that Kofa embraced jihadist ideology after his visit to Pakistan, where he was influenced by the ideology of the Pakistani Jamaat-ud-Dawa, founders of the Lashkar-e-Taiba group active in the Indian subcontinent.[6]

Upon his return to Mali, he established a Fulani-language radio station, taking advantage of his travels between villages and his local language speeches to spread his ideas among Fulani youth. He then founded his group, the Macina Liberation Front, whose primary goal was to revive the once-prosperous Islamic kingdom of Massina, which included the Fulani people.

All these groups merged into a single entity in 2017 under the name Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (Support for Islam and Muslims). Iyad Ag Ghaly was announced as the leader of the group, which pledged allegiance to Ayman al-Zawahiri, leader of al-Qaeda, Abu Musab Abd al-Wadud, leader of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, and Hibatullah Akhundzada, leader of the Taliban.[7]

Formation and Leadership of ISSP

On May 13, 2015, the Tawhid and Jihad Group, a founding member of Al-Mourabitoun, announced its split and pledged allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, under the leadership of Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahrawi.

Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahrawi was born in the city of Laayoune in Western Sahara. He lived in the Sahrawi refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria, and received military training with the Polisario Front. His name rose to prominence with the emergence of the Unity and Jihad Movement, for which he was the official spokesperson in 2011.[8]

With the alliance of the Tawhid and Jihad Movement in 2013 with the Masked Men group, known as the Mourabitoun, led by Mokhtar Belmokhtar, Al-Sahrawi lost his position on the Shura Council. It became the emir of a battalion within the new organization.

In 2014, the Islamic State emerged in Libya. One of the organization’s most prominent figures, Abu Ayman al-Anbari, a close associate of al-Baghdadi, was sent from Iraq. In early 2015, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi accepted the group’s pledge of allegiance in Libya.

During this period, many branches began pledging allegiance to the Islamic State Organization and competing with al-Qaeda in its traditional strongholds. Simultaneously, al-Qaeda initiated a new strategy to counter the ISLAMIC STATE ORGANIZATION, particularly in Africa. At that time, Abu Bakr Shekau’s relationship with al-Qaeda was extremely tense, especially after the organization denied Shekau’s brutality and severed ties with him in 2013. In March 2015, Shekau pledged allegiance to the Islamic STATE ORGANIZATION in Nigeria.[9]

Al-Qaeda sought to persuade Mokhtar Belmokhtar to return and operate under the group’s name after severing ties with it in 2011, while maintaining his organization’s independence. During the negotiations between Mokhtar Belmokhtar and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Sahrawi took advantage of these factors and announced his defection and pledge of allegiance to the Islamic STATE ORGANIZATION in May 2015.[10]

The conflicts within the groups in the Sahara did not arise suddenly, but rather date back to many years of conflict between the desert princes and the senior leaders of Al Qaeda, and with the non-Algerian elements, with Algerians dominating the organization.

This explains the Sahrawis’ independence in the first phase within the Tawhid and Jihad Movement and their subsequent attempt to transform the Al-Mourabitoun movement into the Islamic State.

Unlike Mokhtar Belmokhtar, who is considered a veteran of the Afghan jihad during the Soviet era and who, despite his independence, has maintained his allegiance and loyalty to the Taliban and Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan, Sahrawi is considered more radical and closer to the ideology of the Islamic State.[11]

Al-Sahrawi defected with 100 fighters from Al-Mourabitoun, and the majority refused to follow him and preferred to stay with Mokhtar Belmokhtar. Al-Sahrawi was counting on the power of the Islamic State Organization propaganda during that period, when the organization reached its media and geographical influence[12]. Al-Sahrawi’s areas of activity within the Lake Chad Basin (Nigeria, Niger, Chad) put him close to Shekau, and the border triangle area between Libya, Mali, Niger, and Algeria put him close to the powerful organization in Libya at that time, especially since the Fezzan province in the far southeast of Libya was a province affiliated with Islamic State Organization and an important center for launching operations and withdrawals.

The Sahara branch was initially active under the command of Boko Haram West Africa Province, until the Sahara branch grew stronger and many local fighters who were disaffected with Al Qaeda and fled Libya after the decline of the organization and the flow of weapons and money to it from Libya flocked to it, making the Sahara branch a powerful force that proved this through the many operations it carried out, until the Sahara branch gained its independence and became known as the Greater Sahara Province (ISGS).[13]

In 2021, French President Macron announced the killing of Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahrawi by drone during a French military operation in Mali[14], and the group announced the appointment of Abu al-Baraa al-Sahrawi in his place[15].

All these stages went through a chronological sequence, beginning with a phase of subordination to the West African State, which was called the Greater Sahara State. In March 2022, the organization changed its name to become the Sahel Province Organization[16].

Ethnic and Tribal Composition

JNIM’s Ethnic and Tribal Composition

Since its inception, JNIM has sought to include various local ethnic groups present in the Sahel and Sahara. The central leadership of the JNIM coalition includes Tuareg Arabs (Iyad Ag Ghaly from the Ifoghas region of Kidal), Fulani (Mamadou Koufa of the Macina Front), Berabiche Arabs (northern Mali)[17], and the traditional component of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (Mokhtar Belmokhtar of the Al-Mourabitoun from Algeria).[18] This diversity in the organization’s leadership provides comprehensive representation of most of the ethnic groups in the region where JNIM operates, providing it with numerous advantages, such as popular support and representation of the issues of these marginalized groups.

This is evident in the JNIM strategy of the Messina group, which has taken control of central Mali by exploiting the marginalization and grievances faced by Fulani herders in the Mopti and Ségou regions.

The Macina Front also has a branch, the Burkinabe Support Group for Islam, known by the abbreviation “Katibat Hanifa,” founded by a Fulani preacher in Burkina Faso. This brigade has expanded its operations to northern Benin and Togo[19].

Many fighters from the Maghreb countries (Libya, Tunisia, Morocco, Mauritania, Algeria) are active in supporting Islam and Muslims, either with Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, the Sahara branch, or with Mokhtar Belmokhtar or with Iyad Ghali’s Ansar Dine movement[20].

The Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims (JNIM) is primarily composed of ethnic groups from the Sahel and Sahara regions, as well as West Africa in general. It delegates operational areas and leadership to members of the local ethnic communities, enhancing its effectiveness in field planning for operations and movements. This strategy also attracts fighters from targeted regions and fosters a popular support base for the organization.

ISSP’s Ethnic and Tribal Composition

Al-Qaeda differs from the ISLAMIC STATE ORGANIZATION. Al-Qaeda’s strength was previously attributed to its decentralized organization, unlike the ISLAMIC STATE ORGANIZATION, which gained its strength from its centralized structure. This will be reflected in its ethnic components, particularly in the organization’s leadership.

At the leadership level, the Sahrawis (Western Sahara) monopolized the leadership of the Sahel branch. After the killing of Abu Walid al-Sahrawi in 2021, Abu al-Baraa al-Sahrawi was appointed as his successor. A Shura Council leads the organization, divided into four sections: the Office of Law and Sanctions, the Military and Operations Office, the Office of Foreigners, and the Logistics Office. The structure of the council is dominated by Sahrawi components, whether from Western Sahara, Arabs of the Greater Sahara (with Sahrawi Arab origins or Arab Berbers spread across northern Mali or southern Mauritania)[21], Tuareg with an Arab background (such as Mauritanian lineages), with some Algerians, or Tuareg Berbers[22].

Although the organization has kept the true names and information of its leadership secret, it is likely that many of the leading figures in Libya, such as Libyans and Tunisians, will join the Sahara branch.

The organization relies on fighters it recruits from the Touloub Fulani tribe (located in the Tillabéri region of western Niger and parts of eastern Mali, with pockets in northeastern Burkina Faso).[23] This tribe practices a nomadic lifestyle based on traditional herding of livestock, particularly cattle, which distinguishes them from the urban-based Fulani.

These tribes are considered the organization’s military backbone, and its soldiers carry out most of its operations. They are known as “Ansar,” meaning they are natives of the geographical area and embrace the migrants, who are foreign fighters.[24]

The Islamic State’s structure is diverse and depends on the Fulani herdsmen, taking advantage of the grievances they experience, while also exploiting their issues and conflicts with the Tuareg. However, it centralizes leadership within a governing body connected to a Shura Council, which is in turn subordinate to the organization’s Middle East branch.

Goals, Ideology, and Strategic Differences:

JNIM’s Goals and Ideology:

The Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims (JNIM) is considered a branch of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), which itself is regarded as a branch of the parent organization in Afghanistan. Therefore, JNIM adheres to the same strategy as the parent organization, which has undergone numerous changes over recent years, upon the founding of JNIM.

Iyad Ag Ghaly stated that the organization’s primary goal was to combat what he called the Crusader presence in the Sahel (referring to French forces) and the secular governments in the region that do not implement Sharia law[25].

Ultimately, the establishment of a Sharia-based government in Mali and its environs. Ag Ghaly summarized his founding speech as a movement “to stand up against the occupying Crusader enemy” [26]in defense of Islam.

As for ideology, the organization adopts the Salafi-jihadist ideology of al-Qaeda, which al-Qaeda in Maghreb declared in its correspondence with Bin Laden to gain recognition from its parent organization. The organization is based on a fatwa issued by the Tawhid and Jihad website, which was authored by the Jordanian sheikh Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi[27], the spiritual father of the jihadist movement.

This ideological orientation is seen as more flexible and less rigid than that of the Islamic State. It aims to establish a rule based on Sharia law while also accepting negotiations with governments and engaging with local communities through alliances with other groups that do not share their ideology[28]. It even adopts the rhetoric of marginalized and oppressed communities, presenting itself as a solution and official spokesperson for these groups.

To achieve its goals, JNIM has adapted its ideology to avoid excessive excommunication of local communities, so as not to spill their blood or engage in conflicts with them, and to gain popular acceptance, which represents a popular incubator for it and facilitates the establishment of its future project to rule a region.

ISSP’s Goals and Ideology:

The Islamic State in the Sahel is a province of the Islamic State in the Middle East, subject to its authority and aiming to establish a province within the caliphate. The group’s goal in the Sahel is to eliminate Western influence and apostate governments in the region and establish Sharia law under the Islamic State’s caliphate.

In contrast to Nusrat al-Islam and Muslims, the Sahara Province has shown great severity towards dissenters. It does not form alliances and only recognizes those who fall under its authority. It rejects any kind of negotiations with governments or even other groups in the region[29].

Ideologically, while they belong to the same Salafi-Jihadist family, the Islamic State’s sources differ. It derives its ideological vision from writings such as “The Management of Savagery” and “The Jurisprudence of Blood.” [30] This is evident in the organization’s strategy, which considers anyone who disagrees with or opposes it an apostate, making their blood permissible.

This explains, at first, Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin’s silence on the Sahara Province organization, and even its cooperation with it in some operations, which was called in research circles the “Sahara exception.” However, the Sahara organization began to hunt down members of the “JNIM,” especially after pressure from the organization in Iraq and the Levant not to deal with and to confront the branches of Al-Qaeda, which it considers “apostate militias.” [31]

Conflicts began between the two groups, and “JNIM” accused the Sahara organization of being a “Khawariji” organization. The goal of the Islamic State Organization is to establish a desert province affiliated with the caliphate in Syria and Iraq, using the same strategies as the parent organization, imposing a strict, intolerant system of governance. [32]

Unlike Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin, which maintains a degree of independence from the central organization, the desert branch of the Islamic State is tied to a strict bureaucratic system that is closely aligned with the central organization in Iraq and Syria in all its activities.

Key Differences in Approach:

In summary, JNIM’s ideology and strategy have been characterized by a degree of flexibility and localism, integrating tribal politics. It has repeatedly expressed its desire to engage in dialogue with the Malian government to negotiate or reach a truce, while working to gradually transform communities to adopt its ideology.

This has been evident on numerous occasions, including its conclusion of local non-aggression pacts with community defense militias (such as some of the Donsu hunter-gatherer militias in Mali), and most recently with the secularist MNLA to fight common enemies such as the ISLAMIC STATE ORGANIZATION, the Malian army, and Russia’s Wagner Group[33]. Also, JNIM always issues the local leadership on the scene and gives it authority over its regions, such as Iyad Ag Ghaly and Amadou Koufa.

In fact, this approach is not a new approach, but rather is rooted in the ideology of Al-Qaeda, which was active in Afghanistan within the local Taliban movement and also established many relationships with tribal communities at that time. Also, the first nucleus of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb in northern Mali established many alliances since its arrival in the region in 2003 through marriages with the local community (Mokhtar Belmokhtar) and an alliance with tribal leaders. Also, the locals were benefiting from the commissions they obtained from the exchange of Western prisoners with the organization by playing the role of mediators, despite being from outside the organization.

During the entire period of Amadou Toumani Touré’s rule (2002-2012), the Al-Qaeda-affiliated groups based in northern Mali did not clash with the Malian government, which turned a blind eye to them. They did not move against the Malian government except during the coup against Toumani, and initially allied with the secular Azawad Movement at the time. The movement was also under the name of a local group, Ansar Dine, led by Iyad Ag Ghaly at the time.

There was a tacit alliance with the Malian government, and Toumani was even accused of receiving a commission from al-Qaeda’s operations in the Sahara for Western hostages[34].

Similar to the Islamic State, which follows a more stringent policy to establish a caliphate, showing no tolerance for its opponents and rivals, and without agreeing with groups outside its organizational framework.

Also shows no leniency or tolerance toward local communities, especially those he considers to be cooperating with government forces. He also refuses to enter into negotiations with any government entity and considers Nusrat al-Islam and al-Muslimeen’s acceptance of negotiations with the Malian government a betrayal of the fundamental principles of jihad.

These different approaches between the two groups highlight a fundamental difference in doctrine, goals, and even strategies. While Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (Support for Islam and Muslims) seeks to play on the ethnic and tribal balances in its areas of operation and attempt to win them over and integrate them into its project by making them active and leading players, the Islamic State in the Sahara prioritizes territorial control and imposing a strict regime on the groups under its control through force and intimidation.

Conflicts and Clashes Between JNIM and ISSP:

Despite an initial period of coexistence, JNIM and ISSP eventually descended into open warfare with one another, adding a layer of intra-jihadist conflict to the Sahel’s security crisis.

Sahelian exception phase (2017-2019):

Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb’s (AQIM) strategy has generally been to avoid conflict with splinter groups, considering them members of the jihadist family and able to cooperate with them during times of crisis. This is what happened with most splinter groups, such as Mokhtar Belmokhtar’s split in the past. Even when Sahrawi split from Mokhtar, no clashes occurred between the two sides, and they continued to cooperate on some issues.

On October 30, 2016, al-Sahrawi’s pledge of allegiance was accepted by al-Baghdadi, the leader of the Islamic State, and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara was established. A few months later, in March 2017, the establishment of Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) was announced, and the group pledged allegiance to Ayman al-Zawahiri (the emir of al-Qaeda), Abu Musab Abd al-Wadud (the emir of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb), and Hibatullah Akhundzada (the emir of the Taliban).

Although this period was the height of conflict between al-Qaeda and Islamic State Organization branches around the world, the Taliban was engaged in a major conflict with ISLAMIC STATE ORGANIZATION -Khorasan, and the Islamic State Organization Central was also engaged in major conflicts with al-Qaeda branches in Syria. [35]

Africa itself was one of the largest and most important battlegrounds for these jihadist movements. Libya was the site of the most significant of these battles, as the first branch of the Islamic State Organization was established in Africa.

One of the most prominent leaders of the central organization, Abu Nabil al-Anbari, al-Baghdadi’s right-hand man, visited the country. During 2015-2016[36], Libya witnessed major battles between the Islamic State Organization and groups affiliated with al-Qaeda, including the Abu Salim Martyrs Brigades and the Derna Mujahideen Shura Council[37].

In East Africa, fighting was also ongoing between al-Shabaab, the al-Qaeda affiliate, and the Islamic State in Puntland, led by Abdul Mumin, a defector from al-Shabaab[38].

In West Africa, at the same time, the conflict was between the Islamic State’s West Africa Province and Boko Haram, led by Shekau[39].

This explains why Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin did not clash with al-Sahrawi and did not become involved in this conflict, despite his closeness to them. This is due to al-Qaeda’s dissatisfaction with Shekau’s bloody approach and its severing of ties with Boko Haram in 2012.

As for the situation in the Sahel, at that time, the French Operation Barkhane was targeting jihadists, alongside the G5 Sahel alliance (Chad, Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Mauritania), along with the international campaign led by the United States against Islamic State Organization and jihadist movements worldwide.

All these circumstances created what was called the ” Sahelian exception,” which was the only one in which there was cooperation between the Islamic State Organization and Al-Qaeda. During this phase, JNIM and ISSP fighters occasionally coordinated or conducted parallel operations.

At least five instances of operational cooperation have been documented, such as the ambush in Tongo Tongo, Niger, in May 2019. Wilayat (Province) al-Sahara claimed responsibility for the operation that killed four US Special Forces Green Berets and several Nigerian soldiers[40]. A local brigade loyal to Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) participated in the operation and shared the spoils[41].

The longstanding ties between the fighters and their regional connections facilitated this cooperation, and during this period, field commanders from both sides favored cooperation against French and local forces at the expense of organizational and ideological differences.

This cooperation has been dubbed the “Sahelian exception,” as it deviates from the basic rule, which is the clash between the Islamic State and al-Qaeda. Therefore, the Sahel region appears to be an anomaly dominated by pragmatism and realism.

Breakdown and All-Out Turf War:

In mid-2019, when the Greater Sahara Province had become more deeply embedded within the Islamic State bureaucracy and was incorporated as a branch of the West Africa Province, there was pressure from the central organization on the Sahel Province not to cooperate and to show hostility towards al-Qaeda’s branches in the region.

As this alliance collided with ideological pressure, it also clashed with various regional interests and objectives, and many of its leadership elements and soldiers defected. One of the most powerful blows ISLAMIC STATE ORGANIZATION -Sahara dealt at the time was the inclusion of a large group of Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin fighters (including Fulani elements from Koufa’s Macina group and members of Ansar al-Islam in Burkina Faso) into its ranks.

The Islamic State Organization also began expanding into areas that JNM considered to be under its traditional influence[42].

The Islamic State Organization also began expressing reservations about JNM’s alliances with other groups outside the jihadist movement and its acceptance of the principle of negotiating with the Malian government, leading it to level ideological charges against it, such as apostasy and Murji’ah[43].

JNIM also began to express its leaders’ dissatisfaction with the expansion of the Greater Sahara Province at the expense of its geographical and military base. All these factors ultimately led to a clash between the two sides, with violent battles erupting in approximately 125 incidents between 2019 and 2020, during which more than 731 jihadists were killed on both sides[44].

The most intense of these battles took place in Niger’s interior (Mopti) in early 2020, where the Macina Brigade of the Group (JNIM) expelled Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) cells from several areas, ensuring the group’s control over most of central Mali.

Survivors of the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) in that region withdrew to pockets on its outskirts (such as remote areas of the Mopti region). The conflict spread to parts of northern and eastern Burkina Faso, where splinter factions of Ansarul Islam Burkina Faso, which had pledged allegiance to ISSP, fought with units linked to the Group to Support Islam and Muslims (JNIM), for control of villages and forests along the border between Burkina Faso and Niger. [45]

However, the most significant fighting took place in the “tri-border area” between Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso (the Liptako Gourma), Islamic State Organization propaganda has dubbed the “Triangle of Death.” [46]

In this region—which includes the Gao and Menaka regions of Mali, the Tillabéri region of Niger, and the Sahel region of Burkina Faso—the two groups competed for key transit routes, smuggling corridors, and the allegiance of local communities. The Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) made significant advances in eastern Mali (Ménaka), while JNIM attempted to control areas further west and south. [47]

The result by 2021 was that ISGS had established a presence in parts of Menaka (after defeating local JNIM-aligned militias there), while JNIM maintained a broader presence in central/northern Mali and most of Burkina Faso. [48]

The conflict within the jihadist family has, at times, significantly weakened the two jihadist movements. It has diverted manpower that could have been used against their common enemies and exposed fighters to greater pressure from counterterrorism agencies as they engage in fierce battles.

For example, French forces (Barkhane) exploited the war between JNIM and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara, targeting fighters from both groups as they battled each other, killing hundreds (more than 400 JNIM fighters and more than 200 ISIL fighters in 2020 alone). [49]

By 2021, there were indications that the intensity of clashes between JNIM and ISLAMIC STATE ORGANIZATION -GS had stabilized or become geographically limited, although rivalry persisted. Both groups took distinct stances toward each other, with Islamic State Organization media labeling JNIM as “apostate al-Qaeda militias” and JNIM labeling ISLAMIC STATE ORGANIZATION -GS as “Khawarij.”

Recent Developments:

In 2021, there were signs that the intensity of JNIM-ISSP clashes had plateaued or become more geographically limited, though the rivalry persists.

During the years 2022-2024, the most notable development in the region was the withdrawal of the French Barkhane forces, which left a vacuum in the area that jihadist groups sought to fill. The Islamic State group in the Sahara Province took advantage of this vacuum, particularly in the Menika region. It attacked other armed groups cooperating with the Barkhane forces, such as the Tuareg-led Azawad Salvation Movement (MSA) and its allied self-defense groups, committing massacres against civilians from the Tuareg Daoussak tribe, who are accused of supporting these militias.

On the other hand, [50] JNIM continued its operations against government forces and expanded further, while avoiding a clash with the Islamic State Organization in the Sahel region of Menika. At the same time, it began to take a serious approach to forming alliances and agreements with other groups between 2022 and 2023, such as a de facto non-aggression pact between JNIM and some armed groups in northern Mali (including former separatist rebels of the Azawad Movement) to counter the expansion of ISLAMIC STATE ORGANIZATION[51]. In early 2025, it transformed into a military alliance with the MNLA.

Since 2024, fighting between the two sides has been characterized by intermittent, rather than regular, clashes in their border areas. Neither side currently has a clear strategy for fighting each other, instead focusing on fighting government forces and expanding its influence beyond the other.

Although fighting between the two sides has been avoided for now due to their past experiences, particularly because their greatest losses in human life resulted from their conflict with each other, rather than from their battles with French forces, the current government forces, and Wagner.

However, in the future, it will be impossible for the two sides to coexist side by side due to the intense ideological hostility between them and the ambitions of each, especially the ISLAMIC STATE ORGANIZATION, which believes that all Muslim groups must comply and join its ranks.

Strategic Objectives and Tactics

JNIM’s Strategic Objectives and Tactics

JNIM pursues a dual strategy of insurgency and insurgent governance aimed at gradually expanding its influence. As we mentioned, Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin was established specifically to combat the foreign presence in the Sahel and Sahara region (foreign forces), weaken local armies in the short term, and establish Islamic rule throughout the region. This is an expansion of Al-Qaeda’s goal of establishing a Sharia-based government in the Azawad region (northern Mali). Unlike the ISLAMIC STATE ORGANIZATION, JNIM has not yet declared itself a functioning political and institutional entity (a state), but rather often operates through shadow governance (parallel administration). In contrast, the formal state structure is weakened. [52]

Tactics: Militarily, JNIM employs classic guerrilla tactics adapted to the Sahel’s terrain. These include ambushes on military convoys, improvised explosive device (IED) blasts on roads, and coordinated raids on remote army outposts. [53]

JNIM has shown effectiveness in complex attacks: its fighters have overrun multiple forward operating bases across central Mali and northern Burkina Faso, often taking weapons and vehicles. In 2019, in coordination with ISSP, JNIM operationalized concurrent offensives that overran dozens of military bases in the tri-border area, compelling several government retreats[54].

During this recent period, JNIM has focused its attacks on military bases, initially launching drone attacks, followed by armed raids, looting equipment and weapons, and capturing military personnel. Its most recent operation occurred in early June 2025 in Mali.

On the one hand, kidnapping for ransom is one of the group’s most prominent tactics, a legacy of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), which was known for abducting numerous Western nationals and making huge sums of money from them. However, Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) does not currently have any Western hostages. Instead, it holds two Ukrainians from the Donbas region who are mining gold for Russia, along with Malian military hostages[55].

As for suicide operations, they have declined significantly, and the group no longer relies on them as much as in the past, compared to other jihadist groups. However, among its tactics is its involvement in ethnic conflicts through the Macina group. It has targeted the farming communities of the Bambara and the Dogon in central Mali under the guise of punishing anti-Fulani militias, allowing it to root itself also as a supporter (though an extremely violent one) of Fulani pastoralists. JNIM tactically leverages such grievances – attacking vigilante groups or rival tribes – to win recruits and intelligence from sympathetic populations. [56]

The university’s economy relies on a mix of activities that overlap with those of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), such as smuggling in the Sahara, taxing markets and transit routes, taxing artisanal gold mining sites, and kidnapping for ransom. Reports estimate the organization’s annual income from these activities to be between $18 and $35 million[57].

These revenues support the group’s military strategies and operations and facilitate its recruitment of smugglers and local community leaders. In terms of recruitment, Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimeen relies on its local allies and their rhetoric, such as that of preacher Amadou Koufa, who frames the jihad as a defense of Muslim communities against corrupt states and predatory militias. [58]

The media apparatus also works to strengthen JNIM, represented by the Zallaqa Foundation (founded in 2017), which speaks local languages (Arabic, Fouladi, Tamasheq, Bambara)[59], along with the Andalus Foundation (founded in 2008), the media arm of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, to broaden its appeal. [60]

Importantly, JNIM recruits new fighters through not only ideological ties but also familial ties (e.g., through marriage) and asymmetric military advantages (i.e., protection). Entire villages have been swayed, as JNIM declares that it will respect anyone who does not fight back—essentially a form of intimidation and a means of establishing some social order. In the areas under its control and influence, JNIM typically implements simplified governance for population control. [61]

This may include appointing local and village amirs (commanders) to maintain order, establishing a Sharia court to settle disputes, or enforcing arbitrary social conduct (prohibiting alcohol, forcing women to wear a veil, etc.). However, JNIM’s governance is not generally as publicly institutionalized as that of the ISLAMIC STATE ORGANIZATION; it often allows local chiefs or key actors to persist as long as they operate under JNIM’s governance and pay some form of zakat (tax) to the Jihadists. [62]

This indirect rule method allows JNIM to exercise control through influence instead of a formal takeover, which is a useful strategy for muting possible local backlash. In summary, JNIM’s practices are a combination of insurgent violence with strategic outreach. Instead of wanton brutality when unproductive for action, JNIM relies on targeted coercion.

For example, it may destroy a village aligned with a hated militia (to make a point to other communities), but in the neighboring village, JNIM will circulate leaflets guaranteeing the residents that they will be safe if they do not work with the army. Over the years of insurgency, JNIM has demonstrated resilience, as it can just as easily move as well as being an area, and has shown continual strength. By late 2023, JNIM was even able to strike within the capital district of Mali (attacking a gendarmerie school in Bamako), demonstrating that it has also developed its tactics to include urban terrorism as well as rural guerrilla operations. [63]

ISSP’s Strategic Objectives and Tactics

ISSP/IS Sahel Province’s strategy focuses predominantly on militant expansion and conquest, aligning with the Islamic State’s global objectives. In the Sahel, ISSP specifically aims to seize and maintain territory, impose its interpretation of Sharia, eliminate all competition—whether state or non-state—and ultimately aspires to transform the Sahel into a definitive province of the Islamic State caliphate. In pursuing these goals, ISSP has not engaged in political discussions, nor are there prospects for compromise solutions.

As a militant group, it necessitates a degree of military entrenchment and terror to pacify populations. A French analysis of ISSP at its peak referred to it as “enemy number one,” citing over 400 regional soldiers killed in just one year due to relentless attacks[64], indicating that ISSP’s immediate goal was to break the will and capacity of local security forces.

Tactics: ISSP uses very aggressive tactics that display mobility and shock. One well-known tactic includes large raids on military barracks and gendarmerie posts involving dozens of fighters on motorcycles attacking on multiple fronts. As an example, ISSP claimed an attack in December 2019 on the Inates military camp in Niger, killing at least 71 soldiers, and briefly hoisting its flag upon the completion of the attack. [65]

These attacks, which mix heavy firepower and suicide components, reflect the ISLAMIC STATE ORGANIZATION’s operational approach in Syria/Iraq. ISSP has demonstrated an interest in massacre-type attacks against civilian populations, especially against groups the group identifies as supporting the enemy. In early 2021, ISSP fighters committed unspeakable atrocities in western Niger (the villages of Tchoma Bangou and Zaroumdareye) whereby they killed approximately 100 civilians for cooperating with authorities – a case of collective punishment for shock value. Human Rights Watch reported that ISSP gunmen attacked a camp of displaced Tuareg (Dawsahak) in Mali in July 2024 and executed seven elderly men as retribution against that ethnic group for siding with anti-IS militias. [66]

This tactic of exemplary violence is intended to discourage civilians from supporting ISSP’s enemies. Like JNIM, ISSP also employs IEDs and land mines, although this is not as widely reported, perhaps because ISSP operates in more remote areas with fewer roads. Input against patrols is common; ISSP carried out the infamous October 2017 ambush at Tongo Tongo in which U.S. and Nigerien troops were killed. [67]

Illustrating its prioritization of high-value targets. ISSP has also engaged in kidnapping, but not yet to the extent of AQIM/JNIM on a transnational scale. One notable incident was the May 2019 kidnapping of two French tourists in Pendjari Park, Benin (as an aside, initially by jihadists in the western area where ISSP and JNIM operate); French forces rescued the hostages in an operation in which the involvement of ISSP was suggested.

ISSP has a unique strategic emphasis on exercising territorial control using terror. [68]

ISSP has attempted to clear spaces of competing authority. In practice, this has meant the murder of local leaders, such as tribal leaders or militia leaders who oppose them. For example, ISSP fighters have clashed frequently with Tuareg self-defense groups like GATIA and MSA in Mali, [69] often targeting their leaders for killing.

By executing prominent local resistors and instilling fear in the local populace, it positions itself as the new overlord. While JNIM might use a local leader, ISSP might likely kill a local leader and replace him with a wali (governor) of the Islamic State, or keep the position blank, but under the authority of ISSP gunmen.

ISSP’s recruitment practices have combined ideology with material benefit. In propagandistic terms, ISSP benefits from the Islamic State brand for ideological reasons, which likely will attract the most hardline recruits who understand themselves as part of some global, victorious effort. But, according to reports, ISSP has provided direct material benefits as well: one report indicated that ISSP-linked leaders in Eastern Burkina Faso provided food and medicine to gain favor, and offered cash bounties to people simply for conducting attacks on ISSP’s behalf. [70]

By executing prominent local resistance fighters and instilling fear in the local population, it positions itself as the new supreme ruler. While JNIM may use a local commander, ISSP is more likely to kill a local commander and replace him with an IS wali (governor) or leave the position vacant, but under the authority of ISSP militants. ISSP recruitment practices have combined ideology with material benefits. [71]

Propaganda-wise, ISSP leverages the IS branding for ideological reasons via its Amaq agency, [72] which speaks several local languages, likely to attract more hardened recruits who see themselves as part of a victorious global effort.

However, ISSP has reportedly provided direct material benefits as well: One report indicated that ISSP-linked commanders in eastern Burkina Faso provided food and medicine to garner support and offered cash rewards to individuals simply for carrying out attacks on behalf of ISSP.

Treatment of Local Populations: Governance, Coercion, and Services:

JNIM’s Interaction with Local Residents:

Operating largely in areas long neglected by central governments, JNIM has progressively built a system of shadow governance in zones under its influence. The group is working to establish control and rule over areas through a gradual strategy, presenting itself as an alternative and mediator in local conflicts, and providing protection.

For example, many rural communities in northern and central Mali lack real state courts or police; JNIM acts to fill this justice vacuum by providing Islamic courts to resolve local grievances. Ag Ghaly’s and Koufa’s cadres have established local tribunals that address issues ranging from land disputes to marriage problems according to Islamic Sharia. By resolving land tenancy disputes or punishing cattle thieves, JNIM gains some legitimacy or even qualitative acceptance from civilians who can witness some form of justice being administered (albeit a drastic form of justice). [73]

JNIM also asserts itself as providing security where the state cannot: where there are bandits, its fighters usually remove or kill the common bandits, thereby reducing crime (through terror). As a result, commerce and travel can resume securely under JNIM. This is not unlike the modus operandi of other insurgents affiliated with al-Qaeda that aim to integrate with communities. All of this said, JNIM’s governing takes the form of strict adherence to religious liberty through coercion.

The group has shown a willingness to kill anyone it determines is “spying” or collaborating with the government or French forces. They will execute suspects, often by decapitation or gunshot for effect, to deter others. It has installed social codes similar to those of the Taliban. There have been reports of JNIM cadres in rural Mali setting dress codes (veiling of women), alcohol bans, smoking bans, bans on music, and prohibiting Western-style schooling. Schools in areas affected by jihadists have faced the brunt of this pressure for a variety of reasons: jihadists threaten teachers regularly and have prodded village leaders to shut down these state-run schools teaching a secular curriculum. In fact, by 2019, jihadi pressure (mostly from JNIM and followers) had closed over 2,000 schools across Mali, Niger, and Burkina that had deprived hundreds of thousands of children of an education. [74]

JNIM also asserts itself as providing security where the state cannot: in areas where bandits operate, its fighters usually remove or kill the common bandits, thereby reducing crime. As a result, commerce and travel can resume securely under JNIM. This is not unlike the modus operandi of other insurgents affiliated with al-Qaeda who aim to integrate with communities. All of this said, JNIM’s governing takes the form of strict adherence to religious liberty through coercion.

While JNIM has been represented as more moderate than ISSP, it has a history of severe abuse as well. In central Mali, JNIM units have massacred civilians of communities suspected of being opposed to JNIM. A particularly egregious example occurred in early 2024 when JNIM fighters attacked and burned hundreds of houses in some Dogon villages (Ogossagou area), killing dozens of villagers, for the most part, because these villages were linked to the Dan Na Ambassagou self-defense militia, which broke a truce with JNIM. [75]

As a collective punishment, JNIM punishes whole communities for the avowed compliance of individuals: JNIM sets the tone of their possible punishment for the actions of the individual, but what this means in practical terms is that whole villages are obliterated if any section resists or joins the side of JNIM’s enemy. That said, in areas categorically under JNIM authority, many local people enjoy and experience a sort of day-to-day stability (along with a form of daily fear of decadence).

Even JNIM’s so-called shadow administrations end up allowing villagers to farm and herd while collecting taxes (like zakat on the harvest or herd). JNIM has rules that are somewhat better than Boko Haram in Nigeria, which refuses all western education or dictates that genders cannot interact unless they are violent regarding gender conduct; JNIM’s rules are relatively softer lest they fail to avoid fully isolating the communities they occupy.

JNIM has tended to distribute and/or provide food through the NGO that sympathizes with JNIM through smugglers, or at times, but this is not institutionalized in the way routine governance exists, and an IDP, like in Mali, for example. More frequently, JNIM allows traders to trade as long as they pay dues. JNIM’s legacy of Ansar Dine in northern Mali included the provision of social services in 2012 that included some obligation of care in Timbuktu – administering humanitarian aid and trying to provide a basic local governance model, and that experience informs how JNIM went about their practice. As noted by the International Islamic State Organization Group, JNIM is utilizing “a mainly pragmatic approach, selecting a system of shadow governance which also allows for some local autonomy.” [76]

Villagers under JNIM sometimes keep their local chiefs and daily functions, as long as they accommodate the group. Moreover, JNIM has brokered ceasefires in some cases with community militias– for example, it struck deals with certain Dogon militia leaders to cease attacks on one another. [77]

These agreements can bring respite for exhausted communities that have endured years of violence, demonstrating JNIM’s strategic use of violence and negotiation in controlling the population. JNIM’s treatment of residents is a combination of Islamist governance and rebel pragmatism. Communities are forced to comply through intimidation, such as public executions and social policing, but JNIM is also offering them dispute resolution, protection from banditry, [78] and a sense of social order that the state has failed to provide.

The carrot and stick methods have allowed JNIM to become embedded: many rural localities, while not conventionally jihadist, have conformed to JNIM, learning to tolerate or accommodate itself under JNIM rule, and sometimes to even embrace the alternative stability regarding the humiliation, terror and dispossession of predatory criminals and soldiers, which JNIM dominance provides. And this dynamic is partly responsible for JNIM’s durability in Mali and Burkina Faso.

ISSP’s Interaction with Local Residents:

While ISSP has engaged in some tactical outreach, its overall relationship with local communities has been characterized by violence and intimidation. In areas where ISSP has been or is present, it imposes its ISLAMIC STATE ORGANIZATION-flavored dictates without hesitation or consideration for civilian concerns. Civilian populations face an ultimatum: support the Islamic State’s goals (or at least refrain from opposing them) or be regarded as enemies to be treated as such. There are numerous instances of ISSP fighters gathering villagers and demanding their allegiance under threat of death. Although JNIM – unlike a static village – may engage with a neutral village tactically, ISSP views refusal to cooperate as hostility.

This has resulted in terrible massacres, as seen in Niger’s Tillabéri region in 2021, where ISSP methodically murdered men and boys in villages that had either formed self-defense groups or accepted protection from the state, which guaranteed these communities could not resist in the future. ISSP also employed some ethnic targeting. Its attack against the Dawsahak Tuareg in Mali in 2022–2023, described above, has included village burnings and executions to depopulate areas or force that tribe to submit. [79]

This kind of brutality has caused mass displacement of civilians wherever ISSP is active – tens of thousands of civilians have fled the Ménaka region in Mali and Tillabéri in Niger, fearing the attacks of ISSP. Nonetheless, ISSP does not rely strictly upon terror; it has attempted a rudimentary version of heart-and-minds governance from time to time, particularly after it has consolidated an area. The CSIS analysis indicates that “ISSP has also, in some instances, delivered some governance services where the state has been unable to do so.”

In the case of the Tillabéri region, ISSP operatives mediated land and grazing disputes for farmers and herders, two groups that are generally prone to conflict, and where there are typically no state courts. By adjudicating these types of issues according to Islamic principles, ISSP seeks to establish some type of legitimate authority (even though its broader campaign is violently unjust). In some parts of eastern Burkina Faso, ISSP-linked groups have also reportedly taken some basic social welfare measures, distributing food and medicine to communities. [80]

This can occur after ISSP has intimidated an area into compliance; having neutralized possible opposition, they now seek to win favor by showing kindness to those that are left. It can, in some cases, be a “Robin Hood” thing – for example, protecting Fulani herds from being robbed by thieves (since ISSP has eliminated or co-opted the thieves) and so on, winning gratitude from herders. [81]

ISSP has also given locals direct material benefits for cooperating with them. As was mentioned before, they have handed out cash to motivate informants or provide incentives for some young men to conduct strikes against enemies.

Amnesty International and other human rights monitors have documented ISLAMIC STATE Organization-linked militants executing community leaders (such as imams or village chiefs) who do not endorse them. Human rights monitors also document the ISLAMIC STATE ORGANIZATION’s firearms and civilians abusing or executing those accused of sorcery or moral crimes like adultery. [82]

Essentially, ISSP represents a mix of fear and selective loyalty. Communities that yield and prove useful (for example, by providing recruits and intelligence) may receive what are termed “gifts,” such as protection, humanitarian food aid, or preferential access to smuggling proceeds.

Those who refuse to yield and decide to resist, or who support ISSP’s rivals, can expect ISSP to kill them or target their village with mass violence.

This creates a stark binary distinction, much like how ISSP viewed the two villages I visited on either side of the Mali-Niger border: some Fulani villages accepted ISSP’s narrative and were inducted into their ranks (and even provided with a few lightweight weapons and small arms under ISSP’s auspices for self-defense), whereas villages that would not submit to ISSP, particularly those hosting Tuareg militias or aligned with JNIM, paid a violent price by being massacred. Over time, this binary distinction has forced local people to choose sides for their survival.

To mention this is to highlight that the ISSP’s draconian measures have sometimes boomeranged by alienating communities, which may then seek protection from JNIM or militias undertaking state violence on behalf of the state. The immediacy of revenge following the links of ISSP and indigenous tribes to oppose ISSP (including, but not limited to, the Tuareg Imghad and Dawsahak) demonstrates that many residents of the territory of ISSP viewed them as an existential threat and not a legitimate ruler.

Unlike JNIM, which sometimes prevails as a lesser evil or indigenous rebellion to protect community identity, ISSP is often seen as an alien imposition, “the jihadists who are worse than the state.” Nevertheless, the regions where ISSP has the most firmly entrenched rule (certain zones of Niger and Mali) is so under- served by state presence, that, in these areas, their brutal order is the only order. [83]

Conversely, it quickly carries out massacres and bulk repression to enforce order, showing even less tolerance for dissent than JNIM. Ultimately, this may alienate the majority of the population with ISSP, but as long as people fear ISSP more than they trust the government, ISSP will maintain its power by default. The level of fear ISSP instills is a form of governance, a brutal social contract where the subjects comply to avoid ISSP’s vengeance.

Territorial Reach and Operational Zones:

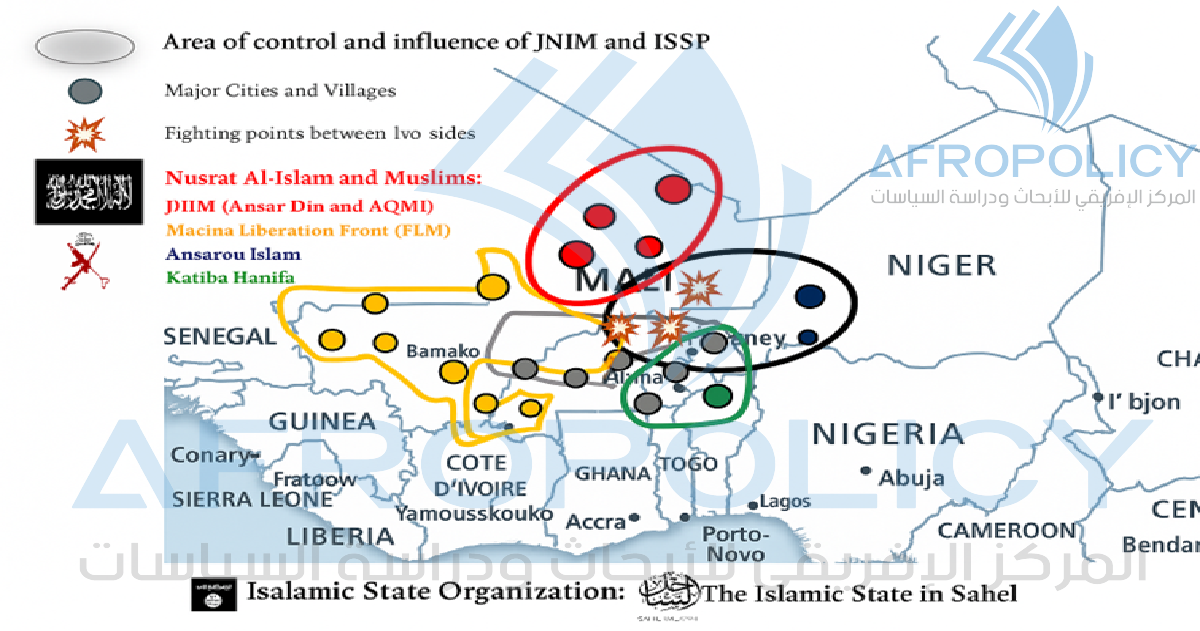

Control Map and Operations Scope of JNIM and ISSP

JNIM’s Geographical Reach: JNIM has progressively extended its geographical reach since its establishment in 2017, expanding well beyond its original vital areas in northern Mali. At present, JNIM and its constituent katibas operate across a considerable geographical portion of the central and western Sahel:

Northern Mali: JNIM (through Ansar Dine and other allied katibas) has large portions of the regions of Kidal, Timbuktu, and Gao either controlled or contested. In Kidal, Ag Ghaly’s forces have considerable operational freedom; sometimes, they have coexisted with or outmatched (to a significant degree) Tuareg separatist CMA forces. [84]

Major towns are still nominally under the control of either Malians or a rebel group, but JNIM has the rural surrounding area in a dominating position. In the Timbuktu region, JNIM influence extends from the desert area directly north of the city of Timbuktu to parts of the Gourma (south of the Niger River). They regularly attack convoys and encircle army outposts, rendering many roads impassable without an escort from the military. Northern Mali has thus been a long-term haven for JNIM, where they impose roadblocks and extract protection taxes on commerce. [85]

Central Mali: Mopti and Ségou (Inner Niger Delta and adjacent areas) were focal points of JNIM activity, though they mostly operated through Koufa’s Macina Liberation Front. JNIM was firmly entrenched and operational in much of Mopti by 2020, having taken over several villages and vast swathes of rural land, while the state had been reduced to a few towns. There were short-lived efforts to dislodge JNIM during offensives in Mali and France in 2020 – 2021, but JNIM has re-established a solid base from which to operate. While JNIM effectively governs areas of the Djenné, Tenenkou, and Douentza circles, elements of JNIM project power across regions from the Dogon highlands (northwards) through to significant sections of the Niger River bends. Human Rights Watch documented JNIM’s attacks on villages in Bandiagara and Bankass, representing some of the most violent attacks on civilians in mid-2024 (burning hundreds of houses), which reaffirmed that JNIM is capable of projecting their power even into areas comprised primarily of rival ethnic populations (in this case Dogon), when those populations take action against them. [86] In Ségou’s northern reaches (around Niono and the Mauritania border), JNIM also established cells, though a 2021 local peace deal briefly eased violence there.

Burkina Faso: Kinship with Ansaroul Islam and affiliates put JNIM on the map. In northern Burkina (in the provinces of Soum, Oudalan, and Loroum), a group—Ansaroul Islam—a group that is formally ‘not JNIM,’ has occupied territory since 2016–2017. This group has practically turned areas like Djibo and Arbinda into jihadist strongholds after the state claimed they lost administrative control. In eastern Burkina (along both Niger and Benin borders), we have also seen JNIM unit infiltration. One of the newer units, known as Katiba Hanifa, has been operating in the Fada N’Gourma area and northern Benin and Togo. JNIM activity in eastern Burkina aims to threaten major road corridors (for example, the route from Niamey to Ouagadougou). [87]

By late 2024, JNIM (likely through Ansaroul Islam) had begun to expand its violence to the southwest of Niger (Tillabéri region), and fatalities there have increased by 237% from the previous year, indicating that JNIM is exploring areas that had historically been impacted by ISSP and possibly encircling Niamey from the west and south. [88]

Coastal West Africa: JNIM has only recently begun to penetrate the Gulf of Guinea states. There have been cells or incursions associated with JNIM as recently as the Kafolo border attack in Ivory Coast (2020), southern Burkina within the border with Ghana, and northern Togo and Benin (attacks against border patrols on numerous occasions in 2021-2022). These early incursions are likely probing for the creation of rear bases or terrorizing coastal governments into acknowledging the Sahelian militants’ reach.

Across West Africa more generally, attacks associated with JNIM have occurred across a “arc of instability” extending from the westernmost parts of Mali (even in Mauritania at times) through central Mali; crossing northern and eastern Burkina Faso; and extending into southwestern Niger. [89]

JNIM-related incidents make up the vast majority of jihadist violence incidents in the Sahel since 2017 – roughly 64% of all militant Islamist attacks in the Mali-Burkina-Niger belt are ascribed to JNIM or its affiliates. [90]

This shows just how far JNIM’s operational theatre is. In terms of territory controlled, JNIM does not generally hold towns for long (to limit their visibility to airstrikes) but controls vast rural areas, operating what some analysts refer to as a quasi-state in the making.

ISSP’s Territorial Footprint: ISSP’s zone of operations has centered on the tri-border Liptako-Gourma region, but with significant spread along borderlands:

Mali (Eastern Regions): ISSP first began as a group active in the Ménaka and Gao regions of Mali. It emerged operating around Ménaka town and remote areas to the Niger border. From the end of 2020, ISSP forces began an intense operation in Ménaka, expanded into the Ansongo area, where they almost eliminated rival Tuareg militias, and allegedly occupied lots of villages and pastoral lands.

By 2022, local media reported that much of the countryside in the Menaka region was, except for ISSP, a no-go area. ISSP also operated in the Gao region’s north in the Talatayet area around the Niger-Mali border. There were records of ISSP travelling even further, as far west as the Mopti region in 2018, but they were subsequently pushed back by JNIM. [91]

In the end, eastern Mali is essentially ISSP’s strongest foothold, with the Ménaka region being the closest thing to territory they hold (though contested by the Malian army and Tuareg fighters). If the new rebellions in late 2023 caused the Malian military to withdraw from some areas in the north, there may have been unfettered movements between Gao and the Ménaka axis for ISSP. [92]

In the end, eastern Mali is essentially ISSP’s strongest foothold, with the Ménaka region being the closest thing to territory they hold (though contested by the Malian army and Tuareg fighters). If the new rebellions in late 2023 caused the Malian military to withdraw from some areas in the north, there may have been unfettered movements between Gao and the Ménaka axis for ISSP. [93]

Niger (West): ISSP has been highly active in Niger’s Tillabéri and Tahoua regions, which border the porous Mali and Burkina Faso borders. Tillabéri – especially the provinces called the “Triomphe” or the three borders area – has suffered hundreds of ISSP attacks, from massacres of civilians in villages such as Tchombangou (Jan 2021) to major attacks on Niger military bases such as Chinagodrar (Jan 2020) and Intagamey. By 2023-24, ISSP seemed to be expanding its footprint in Niger through movement around Niamey: there were reports of ISSP elements infiltrating districts just northwest and east of the capital (Tillabéri and Dosso regions). The Africa Center noted that ISSP may be trying to encircle Niamey by cutting off its supply routes. [94]

Northwestern Niger (Tillabéri) is still the epicenter of ISSP violence and most militant fatalities occurred in Niger (including the Tahoua regoin to its north which has seen attacks (eg., the large massacre in villages in March 2021, killing over 140 innocent civilians)). By late 2024, ISSP has also been operating in southwestern Niger (situated north of Dosso, towards the Burkina border) a placed from which it can clashed indirectly with the JNIM influence making its way from the east of Burkina. [95]

Burkina Faso (North and East): In Burkina, the ISSP has been most active in the Sahel Region (the Oudalan and Séno provinces bordering Mali and Niger). For instance, the Koutougou attack in August 2019 (in which 24 Burkinabè soldiers died) occurred in Soum province but involved ISSP units. [96]

The north of Burkina has seen close competition between ISSP and JNIM. While ISSP has a foothold in the north of Burkina adjacent to Mali, we believe they have cast a net to build-up a presence in the extreme north along the border (tapping into the smuggling networks around Aribinda and in the direction of Niger). In Eastern Burkina (the Est Region) bordering the Niger, and Benin particularly around the tri-border area (i.e. W National Park), there has been an increased influx of fighters attractive to the ISSP. Notably, this influx includes individuals previously affiliated with, or breaking away from, Ansaroul Islam, in addition to recruits. There are reports as recent as 2022, detailing parts of eastern Burkina being largely under effective control of ISSP-linked groups who have also crossed back and forth into Niger and the parks of Benin to launch raids. [97]

Extent of Operations: At its maximum extent, ISSP attacks have ranged around 800 km from central Mali (Mopti) spanning across western Niger to northern Burkina, and about 600 km from Mali’s north down to Burkina’s east. [98]

The central « arc » of ISSP operations is like JNIM’s, but slightly adjusted to the east. Different from JNIM, ISSP had not had any meaningful strike into coastal countries (for example, no indications of ISSP in Ivory Coast), but has gotten very close at Burkina’s and Niger’s border with Benin. ISSP has also not operated in Mali’s far western regions or urban areas like Bamako or Niamey to date (their focus has been on rural or small-town settings). [99]

ISSP has support zones mostly in remote border areas where it has limited opposition (e.g., parts of northern Tillabéri and Ménaka). The contested zones are areas where ISSP engages JNIM or state forces sporadically (such as northern Burkina). Attack zones are places that ISSP can strike but not hold (e.g. further within Niger or Mali). In late 2024, ISSP had expanded a few support zones, particularly in the Ménaka area, taking advantage of the French withdrawal to go on the offensive and taking advantage of the chaos generated from a coup to spread to the new areas.

The group’s volume of attacks is still potentially high: one dataset showed that over one year (May 2019 – May 2020), ISSP conducted 18 large attacks killing more than 400 soldiers in the tri-border area, [100] suggesting that it acts across borders without hesitation.

Outlook for the Future

The trajectories of JNIM and ISSP will significantly shape the security and stability of the Sahel in the coming years. Several factors – recent military interventions (or withdrawals), changing regional politics, and the broader currents of global jihadism – inform the outlook for both organizations:

Impact of Military Interventions and Withdrawals:

After the international military withdrawals from Mali in 2022–2023, most prominently French Operation Barkhane and UN Peacekeepers, security vacuums were formed. The withdrawal of these forces gave incentive for Jihadist groups such as JNIM and ISSP to expand their territorial influence. The decrease in effectiveness for the Mali army was further compounded by the hiring of Russian Wagner Group mercenaries (Currently the African Legion), transforming the counterinsurgency approach in Mali, with argued effectiveness. Military coups in Burkina Faso and Niger had then disrupted regional security cooperation, making the commonly coordinated counterterrorism efforts weaker. As a result of these changes and developments, there has been an increase in insurgents’ attacks and their ability to spread geographically. Overall, the situation in the Sahel has decreased in terms of security, leaving local armies on the back foot and struggling to hold the line under overstretch. Without sufficient support from international organizations looking to address instability and a lack of effective regional security measures, [101] Both JNIM and ISSP will likely continue to exploit the instability around them, with the continued fragility of governments in the region further entrenching them.

Regional Dynamics and Rivalry:

The regional rivalry between JNIM and ISSP is pivotal in determining conflict dynamics in the Sahel. The two organizations began as competitors and shifted towards cooperation until 2019, and as a result of 2019 onwards, there have been almost continuous confrontations and rival ideological assumptions. [102] Though JNIM has a track record of practical partnerships, and at times engaged in negotiations and agreements related to cease-fires with local militias and communities, ISSP has engaged with idiomatic inflexibility and has acted under the banner of ISLAMIC STATE ORGANIZATION; for example, refusing negotiations, and employing violent and depraved forms of violence. The recent events suggest shifting perceptions of alliances. For example, some Tuareg groups appear to be more informally aligned with JNIM, using it as a source of protection from ISSP threats. Each of these dynamics, if unaddressed, has the potential to entrench jihadist groups as deeper actors, provoking a longer-term disruptive conflict, and creating a situation in which civilians experience greater victimization. [103]

Global Jihadist Trends:

Globally, Jihadist groups have shifted focus toward Africa, highlighting the Sahel as a primary battlefield. Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State Organization have actively promoted their Sahel affiliates, underscoring their operational successes and territorial expansions.

JNIM’s alignment with al-Qaeda emphasizes local governance flexibility in its approach and careful expansion. It follows the more flexible approach of Al Qaeda in recent years, based on Bin Laden’s reviews known as the Abbottabad documents.[104]. Al-Qaeda’s branches around the world currently enjoy a great deal of freedom and independent decision-making in the absence of a current leadership for the parent organization after the death of al-Zawahiri.

The limited commitment of JNIM in attacks on Western countries (both Ag Ghali and Annabi have made it clear that France per se was not a target–only French forces in Mali) indicates that it is simply willing to build local emirates, and not provoke serious international outrage. This fits with al-Qaeda’s post-2011 strategy of inciting local insurgency with the intent that they become emirates one day (as was the case with the Taliban or al-Shabaab).

If JNIM achieves quasi-state control over a larger territory, it could become an “al-Qaeda quasi-state”, like al-Shabaab for Somalia; a scenario that Western analysts have argued against. Therefore, if pressure mounts to intervene, external actors could increase support for local armies, or they could push for political settlements.

While negotiating with the Malian government would have significant domestic political problems for JNIM, it could potentially lead to the fragmentation and/or at least the localizing of the jihadist movement. For JNIM’s part, to engage in talks could equally be a way to gain political legitimacy (especially if Ag Ghali thought he would have a public, Taliban role as part of a power-sharing scheme). Any agreement on paper would face considerable pushback from France and countries that offered forces in Mali unless the group can maintain its links to al-Qaeda, which is highly improbable.

ISSP, on the other hand, will be influenced by the path taken by the global ISLAMIC STATE ORGANIZATION network. The Islamic State is regaining its footing in regions of Africa (e.g., IS West Africa in the Lake Chad Basin, IS Central Africa in the Congo/Mozambique). As the ISLAMIC Organization increases its focus on Africa after reversals of fortune in the Middle East, ISSP might find itself with more resources, fighters, or direction. Already, there are signs of some coordination: UN reports have shown the establishment of “joint facilitators” for ISGS and ISWAP, both for training and financing. [105]

If IS or ISWAP sends operatives with experience as commanders or money into the Sahel, ISGS might ramp up its activity. It barely passed without notice, but ISGS rebranded as Islamic State Sahel Province (ISSP), [106] and there has been a notable emphasis by IS on the risks to its West African revenue from states in the region. Taken together, this suggests the ISLAMIC STATE ORGANIZATION intends for the Sahel to be a priority theater. If state inertia continues, it’s possible that more risky attacks will occur, or even attempts to take and hold a major town (as ISWAP did in Nigeria) of regional significance. A bold act of temporarily capturing a regional capital in Niger, or a major town in Mali, cannot be ruled out if the state becomes more destabilized.

Challenges and Uncertainties:

JNIM and ISSP are faced with both internal and external obstacles to their immediate future. JNIM is formed around a coalition structure, with a variety of ethnic groups and interests, meaning that it is plausible that the group could split internally. This could happen after a shift in leadership or a divergence in ideology related to negotiations. ISSP faces sustainability challenges as a result of being the most attacked jihadist group in the Sahel Region, as well as being leaderless due to counter terrorism operations in the region, leading to decapitation of their leadership structures, which is likely to sap organizational cohesiveness. There is uncertainty regarding the possible future military returns of foreign forces, the expansion of counterterrorism campaigns in the region, or even negotiations by some regional governments with jihadists or insurgents. Above all, the persistent political instability of the states in the region and the use of controversial counter-insurgency practices by local armies are aggravating grievances in a way that serves local jihadist recruitment. As such, these challenges and uncertainties will be determinant of whether jihadists can entrench control, be fractured, or face intensified countermeasures by regional or international states.

Global Reach and Ideology: Into 2025, al-Qaeda and the Islamic State Organization are engaged in a kind of rivalry for new relevance, and the Sahel is an important area for both organizations. JNIM successes support al-Qaeda’s narrative of being the clear leader of jihad, with the ability to have persistent grassroots-level insurgents. ISSP’s brutality, in contrast, supports the Islamic State Organization’s narratives of expanding despite losing the heartland of its caliphate. Thus, both groups have the incentive to continue, and amplify, their actions to claim victory in the war of narratives. As long as neither group is decisively defeated, new foreign fighters or at least foreign funding (via supportive networks) will likely be attracted to their presence in the region, further internationalizing the conflict.

Summary:

In the absence of determined changes, JNIM will continue to expand its shadow-governance and insurgent attacks, particularly in Mali and Burkina Faso, slowly expanding into littoral West Africa. It may well coalesce into an increasingly quasi-conventional force controlling rural areas and may seek some measure (de facto if not de jure) of political legitimacy (Syrian Scenario). ISSP will continue to operate as a fluid, high-tempo insurgency in border areas, trying to demonstrate relevance through large attacks and possibly attempting to secure a more permanent foothold if the opportunity presents itself. The rivalry between both groups will continue; however, its intensity (if not its volatility) may ebb and flow.

More than likely, the two will stay rivalry adjacent, although with a fluctuating intensity. One situation to watch is what happens if one group significantly prevails over the other, or how far the two groups can go in competition with each other. For example, can JNIM, which has the advantage of numbers, find a way to isolate ISSP into a few distinct pockets (or vice versa if much of JNIM ends up co-opted by ISSP)? Or are we going to be in an indefinite scenario where both groups have a distinct turf, similar to the al-Qaeda and Islamic State Organization branches in different regions of Syria, after a long time intermittently fighting?

Thus, JNIM and ISSP have quickly become entrenched actors in the conflict ecosystem of the Sahel, and their evolution will be driven by a blend of local action and international action. In the absence of mechanisms for resolving conflict or better governance, both jihadist groups will take advantage of state fragility, and the worry is that the Sahel will experience the establishment of a permanent Jihadist sanctuary across multiple countries, with a range of consequences for regional and global security. On the other hand, a mix of creative diplomacy, including a dialogue with at least one of the groups, with greater accountability to the respective populations in security operations, could eventually shrink their available space. For now, the future implies that JNIM and ISSP will continue to be significant actors of violence and power in the Sahel, navigating between opposing each other and capitalizing on the turbulence to reach their respective end goals.

Comparative Summary Table: JNIM vs. ISSP in the Sahel

| Aspect | JNIM (Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin) | ISSP (Islamic State in the Greater Sahara) |

| Formation

| Founded in March 2017 by the merger of 4 groups (Ansar Dine, Macina Liberation Front, Al-Mourabitoun, and AQIM’s Sahara branch). Al-Qaeda pledge of allegiance (Zawahiri). | It emerged in May 2015 as a breakaway of al-Mourabitoun. While operations were led by Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahrawi, who pledged loyalty to the ISLAMIC STATE ORGANIZATION, it was initially done without formal recognition. Al-Sahrawi’s group was officially recognized by the Islamic State Organization in October 2016; in 2022, it became the separate “Sahel Province”. |

| Leadership

| Emir Iyad Ag Ghaly (Malian Tuareg), with deputies like Amadou Koufa (Fulani). A coalition structure in which the leaders of constituent katibas drive their action. Affiliated with the AQIM hierarchy but operates independently on the ground. | Originally led by Adnan al-Sahrawi (killed in 2021). No publicly named successor operates under the Islamic State Organization’s core guidance. Structured as part of IS’s West Africa division (now a distinct ISSP). More centralized leadership, though cells show some autonomy. |